In my last post, I looked at the cost of capital, a measure of what it costs firms to raise capital. That capital, if put to good use by businesses, should earn returns higher than the costs to generate value. Simply put, the end game in business is not just to make money but to make enough to cover a risk-adjusted required return. In publicly traded companies, it is managers at these companies, for the most part, who are investing the capital that comes from stockholders and bondholders (or banks), and corporate governance is a measure of whether these managers are being held accountable for their investment decisions.

Defining a good investment

It is true that there are differences of opinion about how best to measure the cost of raising funds, but disagreements about the cost of capital are drowned out by disputes on how best to measure the returns that are generated by investing this capital. There are two widely used proxies for profitability. One is the profit margin, obtained by dividing the earnings by the revenues of the firm, and it can be estimated using either operating income (operating margin) or net income (net margin). Since the latter is a function of both the profitability of businesses and how much they have chosen to borrow, I will focus on operating margins and report on the distribution of both pre-tax and after-tax operating margin in the graph below:

|

| Source: Damodaran Online |

The second measure of profitability, and perhaps the more useful one in the context of measuring the quality of an investment, is obtained by scaling the operating earnings to the capital invested in a project or assets to estimate a return on invested capital. The capital invested is usually computed by aggregating the book values of debt and equity in a business and netting out the cash. The resulting return on invested capital can be compared to the cost of capital to arrive at the excess return (positive or negative) earned by a firm. In the figure below, I look at the mechanics of the return on capital computation in the picture below.

Note the caveats that I have added to the picture, listing the perils of trusting two accounting numbers: operating income and invested capital. I did try to correct for the accounting misclassifications, converting leases into debt and R&D into capital assets, and also computed an alternate return on capital measure, based on average earnings over the last ten years. Notwithstanding these adjustments, I am still exposed to a multitude of accounting problems and I have to hope and pray that the law of large numbers will bail me out on those.

I computed the return on invested capital for each of the 41,889 firms in my sample and subtracted out the cost of capital for each one to arrive at an excess return. The graph below captures the distribution of this excess return across global firms in 2015:

I computed the return on invested capital for each of the 41,889 firms in my sample and subtracted out the cost of capital for each one to arrive at an excess return. The graph below captures the distribution of this excess return across global firms in 2015:

Overall, more than half of all publicly traded firms, listed globally, earned returns on capital that were lower than the cost of capital in 2015 and this conclusion is not sensitive to using average income or my adjustments for R&D and leases. The return on capital is a flawed measure and I have written about the adjustments that are often needed to it. That said, with the corrections for leases and R&D, it remains the measure that works best across businesses in capturing the quality of investments.

Industry Excess Returns

In the second part of the analysis, I broke down the 41,889 companies into 95 industry grouping and computed the excess returns for each industry group. The full results are at this link, but I ranked companies based on the magnitude of the excess returns. Again, with all the reservations that you can bring into this measure of investment quality, the businesses that delivered the highest spreads (over and above the cost of capital) are listed below.

The best-performing sector is tobacco, where companies collectively earned a return on capital almost 22% higher than the cost of capital. One potential problem is that many of the businesses on this list also happen to be asset-light, at least in the accounting sense of the word, and some of these returns may just reflect our failure to fully capitalize assets in these businesses.

Looking at the other end of the spectrum, the following is a list of the worst performing businesses in 2015, based on returns generated relative to the cost of capital.

Note that oil companies are heavily represented on this list, not surprising given the drop in oil prices during the year. That, of course, does not make them bad businesses since a turning of the commodity price cycle will make the returns pop. There are other businesses that have been affected by either the slowing down of the China growth engine, such as steel and shipbuilding, and the question is whether they can bounce back if Chinese growth stays low. Finally, there are some perennially bad businesses, with auto and truck being one that has managed to stay on this list every year for the last decade, grist for my post on bad businesses and why companies stay in them.

In computing this excess return, I deliberately removed financial service firms from the mix, because computing operating income or invested capital is a difficult, if not impossible task, at these firms. Lest you feel that I am giving managers at these firms a pass on the excess return question, I would replace the excess return spread (ROIC - Cost of capital) with an equity excess return spread (ROE - Cost of Equity) for these companies.

Regional Differences

Are firms in some parts of the world better at putting capital to work than others? To answer that question, I broke my global sample into sub-regions and computed both operating margins and excess returns (return on invested capital, netted out against cost of capital) in each one.

Looking at the list, the part of the world where companies seem to have the most trouble delivering their cost of capital is Asia, with Chinese companies being the worst culprits and India being the honorable exception. US and UK companies do better at delivering returns that beat their hurdle rates than European companies.

Again, I would be cautious about reading too much into the differences across regions, since they may be just as indicative of accounting differences, as they are of return quality. It is also possible that some of the regions might have a tilt towards industries that under performed during the year and their returns will reflect that. Thus, the excess returns in Australia and Canada, which have a disproportionate share of natural resource companies, may be reflecting the drubbing that these companies took in 2015.

A Case for Corporate Governance

I have been doing this analysis of excess returns globally, each year for the last few, and my bottom line conclusions have stayed unchanged.

- The value of growth: If the value of growth comes from making investments that earn more than your hurdle rate, growth in a typical publicly traded company is more likely to destroy value than to increase value (since more than 50% of companies earn less than their cost of capital). For investors and management teams in companies, I would view this as a signal to not rush headlong into the pursuit of growth.

- Bad management stays bad: In my sample, there are firms that have been earning excess returns year after year for most of the last decade, casting as a lie any argument that managers at these firms might make about "passing phases" and "bad years" affecting the numbers. To the question of why these managers continue to stay on, the answer is that in many parts of the world, it is almost impossible to dislodge these managers or even change how they behave.

- Bad businesses: There are entire businesses that have crossed the threshold from neutral to bad businesses, but management seems to be in denial. These are the businesses that I have described in my corporate life cycle posts as the "walking dead" companies and I have explored why they soldier on, often investing more into these investing black holes.

Is good corporate governance the answer to these problems? In much of the world, the notion that stockholders are part owners of a company is laughable, as corporations continue to be run as if they were private businesses or family fiefdoms, and politics and connections, not stockholder interests, drive business decisions in others.. Even in countries like the United States, where there is talk of good corporate governance, it has become, for the most part, check-list corporate governance, where the strength of governance is measured by how many independent directors you have and not by how aggressively they confront managers who misallocate capital. Institutional investors have been craven in their response to managers, not just abdicating their responsibility to confront managers, where needed, but actively working on behalf of incumbent managers to fight off change. The sorry record of value creation at publicly traded companies around the globe should act as a clarion call for good corporate governance. In the words of Howard Beale, from Network, we (as stockholders) should be "mad as hell and should not take it any more".

Datasets

Paper on measuring accounting returns

Paper on measuring accounting returns

- Paper on measuring ROIC, ROC and ROE (Warning: Extremely boring but could be cure for amnesia. Don't read for excitement value!)

Data Update Posts

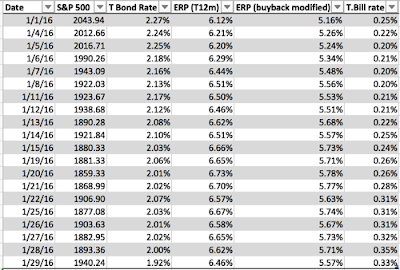

- January 2016 Data Update 1: The US Equity Market

- January 2016 Data Update 2: Interest Rates and Exchange Rates - Currencies

- January 2016 Data Update 3: Country Risk and Pricing

- January 2016 Data Update 4: Costs of Equity and Capital

- January 2016 Data Update 5: Investment Returns and Profitability

- January 2016 Data Update 6: Capital Structure

- January 2016 Data Update 7: Dividend Policy

- January 2016 Data Update 8: Pricing and Valuation