After my last two posts in Tesla, I was planning to take a break from the company, since I had said everything that I had to say about the company. In short, I argued that Tesla, notwithstanding its growth potential, was over valued and that to deliver on this potential, it would need to raise significant amounts of capital in the next few years. In an even earlier post, I described Tesla as the ultimate story stock, both blessed and cursed by having Elon Musk as a CEO, a visionary with a self destructive streak. Even by Musk's own standards, his tweet on August 7 that Tesla would be going private, adding both a price ($420) and a postscript (that funding had been secured), was a blockbuster, pushung the stock price up more than 10% for the day. The questions that have followed have been wide ranging, from whether Tesla is a good candidate for "going private" to the mechanics of how it will do so (about funding and structure) to the legality of conveying a market-moving news story in a tweet.

1. Public to Private - The Why

When we talk about transitions between private and public market places, we generally tend to focus on private companies going public. That is because it is natural and common for a small, privately owned business, as it grows larger, to move to public markets, with an initial public offering. That said, there are publicly traded companies that seem to move in reverse and go back to being privately run businesses, as Tesla may be proposing to do.

The Trade Off

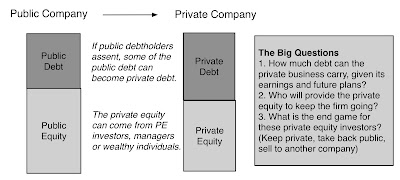

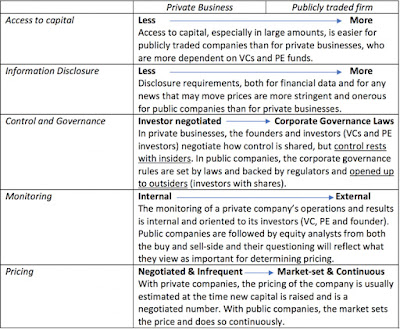

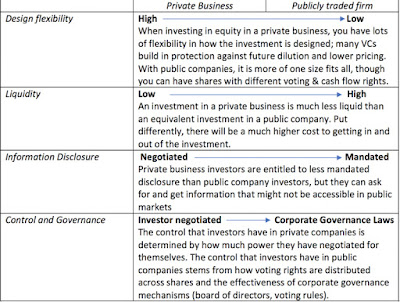

To understand both transitions, the more-common private to public and the less-frequent pubic to private, let us consider the trade off between being a private business and a publicly traded company, from the perspective of the business:

|

| Private versus Public: Business Perspective |

The simple summary is that as a private company's need to access capital increases, it will accept more information disclosure and a more outsider-driven corporate governance structure, and make the transition to being a public company. In recent years, the market for private equity has broadened and become deeper, allowing companies to stay private for far longer; Uber, for instance, is worth tens of billions of dollars and is still a private company. To fully understand the transitions, though, we also have to look at the choice from the perspective of investors:

|

| Private versus Public: Investor Perspective |

In the classic structure of going public, private firms raise money from venture capitalists who accept less liquidity, but structure their equity investments to often get more protection and a bigger say in how the company is run. It is the desire for liquidity that makes venture capitalists push private companies to go public, so that they can cash out their investments. To be able to negotiate better disclosure and control, private company investors have to be investing larger amounts, and it is one reason that regulatory authorities have been wary of allowing small investors to invest in private companies, since they may end up with the worst of all worlds: illiquid investments in businesses, where they have no say in how the company is run, and no information about how well or badly it is doing.

The Public to Private Transition

With this trade off in mind, why would a public company choose to go back to being a private business? This transition makes sense if a company feels that the easier access to capital and a continuously set market price (which delivers liquidity), two features of public markets, no longer provide it with sufficient benefits, and/or the costs of disclosure and outsider intervention (from activist investors), that also come with being a public company, increase. In short, it has to be a company:

- that does not need access to large amounts of new capital to continue operating,

- where the market is under pricing the company, relative to its intrinsic value ,

- that feels the actions that it needs to take in its best long term interests will either create public backlash (layoffs and plant closures) or adverse market reactions (because of the effect that they will have on metrics that investors are focused upon).

It should come as no surprise that most companies that have gone through the public-to-private transition have been aging companies (no growth, no capital needed), trading at prices that are below their peer group (lower multiples of earnings or cash flows) and that need to shrink or slim down to keep operating.

The Tesla Case

As I look at the list of criteria for a good buyout company, I see nothing that would bring Tesla onto my radar as a potential candidate:

- It is a growing company and it needs new capital to not only deliver on its growth promise but to survive for the next few years. If you are more optimistic than I am about Tesla, you may disagree with how much cash the company will have to raise to keep going, but I challenge even the most hardened optimist to tell me how the company will be able to increase production to a million cars or more without investing mind blowing amounts in new capacity.

- If markets are punishing Tesla by under pricing the company, they are doing so in a very strange manner, giving it a higher market capitalization than much larger, more profitable automobile companies, ignoring large losses and generally tolerant of Elon Musk's errant behavior. In fact, if the critique of markets is that they are short term and focused on profits, Tesla would be the perfect counter example.

- It is true that there was substantial drama and market volatility around the 5000 cars/week production target, and there may be some in the company who have the drawn the lesson that since there will be more production targets to come in the future, the company needs to operate out of market scrutiny. That would be the wrong lesson, since almost all of the drama in this episode, from setting the target (5000 cars/week) to the constant tweets about whether the targets would be met, was generated by Elon Musk, not the market. In fact, a cynic would argue that by focusing the market's attention on this short term target, Tesla has been able to avoid answering much bigger questions about its operations.

There are, of course, the short sellers in Tesla and Musk's frustration with them was clearly a driver of his "going private" tweet. His argument, which many of his supporters buy into, is that short sellers in public markets make money from seeing stock prices go down, and that some of them may do real damage to companies, because of this incentive. I will not dismiss this complaint, but I will come back to it later in this post, since I do think it is playing an outsized role in this process.

Public to Private - The Funding

When you decide to take a publicly traded company into the privately owned space, you have to replace the public capital (public equity and debt) with new capital that can be either private equity or new debt.

The key questions then become what mix of debt and equity to use, how to raise the private equity needed to get the deal done and what the ultimate end game is in the transaction. Specifically, you may take a company private, because you want to control its destiny fully, and keep tit a private business in perpetuity. More often, though, the end game is to make the changes that you think will make the company more attractive to investors, and either take it back public or sell it to another public company.

The Analysis

If the company in question fits the buyout mold, i.e., it is an aging company with a lower market capitalization, relative to earnings and cash flows, than its peers, the going private transaction can be funded with a high proportion of debt, explaining why so many buyouts have leverage attached to them, making them leveraged buyouts.

Given that the equity investors in the transactions have to give up public market governance tools, it should come as no surprise that in many of these deals, the private equity comes from a single firm, like KKR or Blackstone, with top managers holding some of the private equity, to align interests, after the deal goes through. Success in these deals comes from taking the reconfigured company public again, at a much higher value, leaving equity investors with outsized gains.

The Tesla Case

Tesla is a money-losing company, burning through significant amounts of cash. Not only is the company in no position to borrow more, I have argued before that it should not even carry the debt that it does. If this deal is to make sense, it has to be predominantly equity funded, but that does create some challenges.

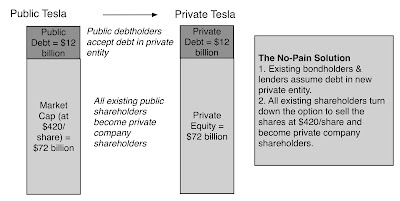

1. The No-pain solution: Musk, in his Tuesday tweets, seems to offer a solution, which, if feasible, would be relatively painless. In his set up, existing shareholders will be allowed to exchange their shares in Tesla, the public company, for shares in Tesla, the private business, and those shareholders who are unwilling to take this offer will sell their shares back to the company at $420/share. In the extreme case, where every existing shareholder takes this offer and if existing debt holders are willing to continue to lend to the new private enterprise, Tesla will need no new funding:

This would be magical, if you can pull it off, but there are two significant impediments. The first is that the deal may not pass legal muster, since the SEC restricts private companies to having less than 2000 shareholders, and Tesla has far more than that number. It is true that you might be able to create a fund that has individual shareholders, which then holds equity in the private company, like Uber has, but that fund is restricted to very wealthy, big investors, and the SEC may be unwilling to go along with a structure where there are thousands of small stockholders in the fund. The second is that even if Tesla manages to get regulatory approval for this unconventional set up, many shareholders may choose to cash out at $420, if the company goes private, even if they think that the shares are worth more, because they value liquidity.

2. A Deep-pocketed Outsider: The announcement that the Saudi Sovereign fund had invested $2 billion in Tesla shares came just before Musk's "going private" tweet, setting up a second possibility, which is the a large private equity investor (or several) would step in to fund the deal. Here, Tesla's large market capitalization and cash burning status work against it, reducing the number of potential players in the game. At the limit, if all existing shareholders, other than Musk, cash out at $420/share, you would need about $55-$60 billion in funding. No sovereign fund or passive investment vehicle can afford to have that much money tied up in one company, and especially one that is illiquid and will need more capital infusions in the future. Even the biggest private equity and venture capital investors, generally more willing to hold concentrated positions, will be hard pressed to put this much capital, for the same reasons. In fact, the only name that you can come up with that has even the possibility of pulling this off is Softbank, for three reasons:

- They may be big enough to make the investment. As a publicly traded company with a market capitalization of $103 billion, making a $55-60 billion additional investment in Tesla would be a reach, but Softbank is capable of drawing other investors of its ilk into the funding.

- They have and are invested in young, growth companies: Unlike traditional PE investors whose focus has been on doing leveraged deals of cash-rich companies, Softbank has invested successfully in growth companies, many of whom continue to burn through cash.

- They have a history with Tesla: There were rumors last year that Tesla and Softbank had talked about taking the company private, but control disagreements caused negotiations to break down.

That said, I am not sure that Elon Musk and Masayoshi Son (Softbank's CEO) can co-exist in the same company. Both value control, and both are unpredictable, and I have to confess that watching the two tango would make for great entertainment.

3. A Corporate Investor: There is one final possibility that I considered and it is that a corporation with deep pockets would provide the money needed to take Tesla private. Given how much money is needed, the list of potential buyers is small and perhaps restricted to the large tech companies - Apple and Google. While they have the cash and perhaps may even have the interest, Musk's follow up that he would continue to run the company and hold on to his ownership stake strikes me as a poison pill that no corporation will want to swallow.

3. A Corporate Investor: There is one final possibility that I considered and it is that a corporation with deep pockets would provide the money needed to take Tesla private. Given how much money is needed, the list of potential buyers is small and perhaps restricted to the large tech companies - Apple and Google. While they have the cash and perhaps may even have the interest, Musk's follow up that he would continue to run the company and hold on to his ownership stake strikes me as a poison pill that no corporation will want to swallow.

It is at this point that the "secured funding" claim that Musk made in his initial tweet comes into question. If the statement is true, he has either found an inept bank that will lend tens of billions to a money losing company with an undisciplined CEO, or a private equity investor who is willing to make the largest PE investment in history, while allowing Musk to continue running the company, with no checks and balances. If the statement is false, we will be seeing lawyers debating the meaning of the words "secured" and "funding" for a while.

Occam's Razor: A simpler explanation

This entire post has been premised on the notion that Elon Musk had done his homework and that he intended to send a serious signal to markets about a future buyout. Given Musk's history of impetuous and personal tweets, that premise might be completely wrong, in which case the explanation for this episode may be far simpler and rooted in the war with short sellers that Musk has been fighting for a while. Musk is convinced, rightly or wrongly, that short sellers in Tesla are conspiring to bring not just the stock price, but the entire company, down. While there are short sellers in every publicly traded company, including the most successful in market capitalization (Apple, Facebook, Google, Amazon), Tesla is an outlier in terms of the short selling on two fronts:

- It has a CEO who is obsessed with short selling and spends a disproportionate amount of his time and attention on bringing them down. So, it is true that short sellers are a distraction to the company, but only because Elon Musk has made it so.

- On the other side, many of the short sellers in Tesla seem to be just as obsessed with Musk and are convinced that he is a scam artist. I have a sneaking feeling that for many of them, winning will mean not just making money on their Tesla positions, but seeing the company cease to exist (and taking Musk down with it). On my Tesla valuation from a few weeks ago, it is telling that the most heated responses that I got were not from Tesla bulls, accusing me of being too pessimistic, but from Tesla short sellers, arguing that I was being over valuing the company, even though my assessed value per share was half the prevailing price.

Investing is a difficult game, to begin with, but it becomes doubly so, when it becomes personal. Just as it is dangerous to fall in love with a company that you have invested in, it is just as dangerous to bet against a company because you hate its management and want it to fail. I think both sides of the Tesla short selling game are so infected with personal bias that they may do or say things that are not in their best long term investing interests. That is why I hope, for Tesla's sake, that Musk's personal dislike of short sellers did not lead him to tweet out that Tesla would go private. with both the price ($420) and the "secured funding" being spur of the moment inventions. In his zeal to make short sellers pay, he may have handed them the weapon they need to bring him down. I know that Tesla's board has backed Musk, saying that he had opened a discussion about going private with the board, but since no mention is made of a price or funding, and given how ineffective and craven this board has been over the last few years, I cannot attach much weight to this backing.

Bottom Line

There are publicly traded companies where going private is not only an option, but a value-increasing one, but Tesla is not one of them. As with so much else that the company has done over its history, from its acquisition of Solar City to borrowing billions of dollars to this talk of going private, it is not the action per se that is inexplicable, it is that Tesla is not the company that should be taking the action. The drama will undoubtedly continue, and in a world where we get much our entertainment from reality shows, the Elon Musk show is on top of my list of must-watch shows.

YouTube Video

Blog Posts on Tesla

Paper on Going Private